John McClane relied on his CB radio survival just like I depend on my iPhone

We often talk as if online collaboration is a new challenge, one minted by hybrid work, Slack and Teams. But the 1988 movie Die Hard remind us that the fundamentals of virtual collaboration aren’t about the technology: They’re about building trust when you can’t see someone face-to-face.

How can we possibly learn about building online trust from a movie that is ten years older than Google, eighteen years older than Google Docs, and nearly thirty years older than Teams?

Well, its prescient insights jumped out at me last year, during our annual holiday re-watch. I was struck by how much of the movie is propelled by an entirely virtual collaboration: the relationship between the movie’s cop-hero, John McClane, and his outside-the-crisis helper, Sgt. Al Powell.

Collaboration tech: 80s edition

The original Die Hard movie centres on a hostage-taking in the Los Angeles office building where McClane’s estranged wife is attending her company Christmas party. After McClane eludes the initial hostage-taking, he puts his cop skills to work with a credulity-stretching but eminently watchable battle against a crew of captor-bandits. His biggest challenge is that he has to battle them alone: The captors have cut the phone lines to the office building, and since this is the bad old days before we all had mobile phones, McClane has no way to call for help.

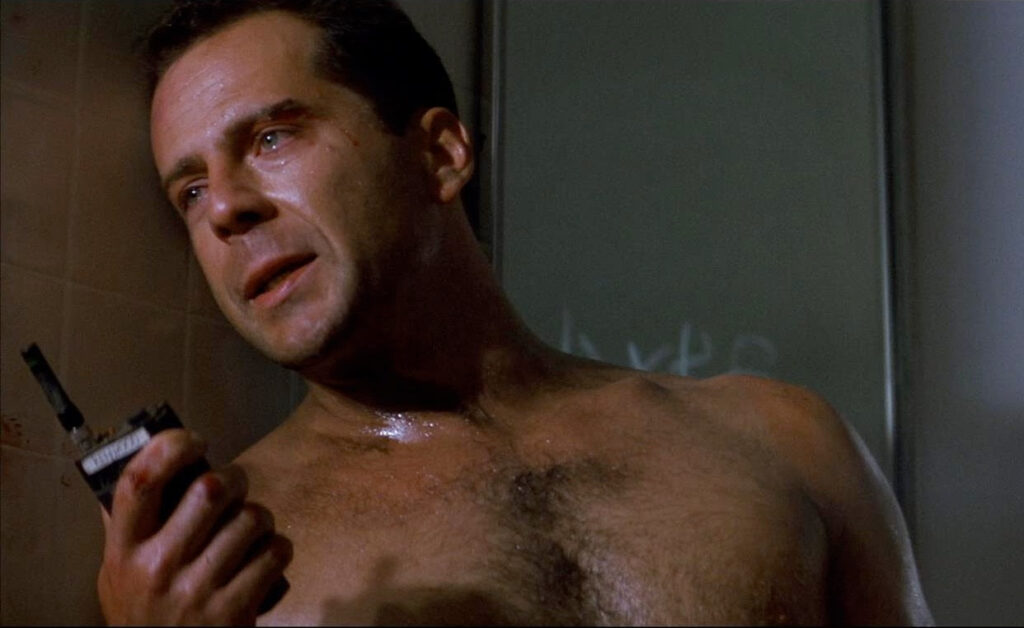

Once McClane takes down one of the bad guys, however, he’s able to snag one of the CB radios the criminals are using to communicate during their heist. (Pity the poor criminals who once had to rely on CB as their best option for mid-heist communication.) He uses the radio to signal for help, and after being scolded by a disbelieving dispatcher for making use of an emergency-only channel, makes contact with the nearby Powell, a beat cop turned “desk jockey” who’s assigned to check on the dubious report logged by dispatch.

The rest of the movie really unfolds as gun-laden, virtual pas de deux between McClane and Powell: McLane on the inside, providing intel on the criminals and their armoury, and Powell on the outside, trying to influence the rescue effort based on what he’s hearing from McClane. While the assembled law enforcement team is mostly skeptical about this unknown voice on the CB, Powell quickly decides that McClane is trustworthy—even though the two have never met—and their allegiance proves decisive.

The relationship between McClane and Powell may be forged via CB rather than over text, email or video meeting, but their dynamic is a lovely object lesson in why trust is so important to virtual teams, and how to go about building trust with someone you’ve never met in person.

Here’s how re-watching Die Hard gives me an annual reminder of how to build trust with my online colleagues.

Ask for help—loudly.

It’s tempting to assume that I can get the help I need on a project, just by inviting a colleague into a draft Google Doc or even by forwarding what should be a self-explanatory email thread. But Die Hard underlined how hard its to get people’s attention, much less their active engagement in a project—especially if you haven’t yet developed a strong collegial relationship.

That’s John McClane’s initial problem in Die Hard—until he grabs Powell’s attention by catapulting a criminal’s bullet-ridden body through a plate glass window and onto Powell’s cop car, many storeys below. That is probably overkill in most of my own projects, though receiving the ALL CAP SUBJECT LINE sure feels like the email equivalent.

I have my own tricks for getting attention when I’m kicking off a new collaboration: For example, I always send a separate email explaining why I’m inviting someone into a draft document (and I let them know exactly what kind of help I’m looking for.) And if it’s a brand-new working relationship, I try to set up a short “getting to know you” call before I put my hand out for help. Asking for help politely and explicitly, instead of just assuming someone will jump in, is fundamental to getting off on the right foot.

Lean into shared reference points.

Die Hard really illustrates how helpful it is to identify the reference points or jargon that you have in common with your colleagues, particularly when you’re collaborating with someone you’ve never met. Building trust is about more than just finding a common language; there’s an immediate intimacy that comes from unlocking something that feels more like a secret code.

A pivotal moment in the movie is when McClane describes the hostage-takers to Powell, using language and precision that feels cop-to-cop familiar. It reminded me of one of my favorite collaborative relationships, with a longstanding colleague I’ve only met in-person once: Most of our conversations unfold in a mix of English and Boolean, and our shared ability to speak in search-engine syntax accelerates our work when we are jointly developing a new dataset.

I have little doubt that McClane would deride both of us as “geeks who could never make the team” (his derisive dismissal of the techies who appear in the later Live Free and Die Hard), but our shared lingo is just as crucial to our professional bonding as Powell and McClane’s shared understanding of fake IDs and perp descriptions.

Bond through adversity.

An abundance of caution means that I’m often reluctant to say anything critical, especially if it might be perceived as gossipy or backbiting….but Die Hard reminds me of the value of a common enemy. After all, nothing builds trust faster than a sense that it’s you and your colleague against the world—and that kind of “swift trust” (as researchers call it) can be hard to come by when you’ve yet to meet a colleague face to face.

In Die Hard, most of the L.A. cops dismiss McClane’s value—but their dismissal helps to forge a bond between Powell and McClane. Precisely because Powell is the only one listening, McClane leans on him harder; and precisely because none of his colleagues will heed McClane’s wisdom, Powell draws closer to McClane.

That dynamic holds a mirror up to what I’ve seen in plenty of offices where underlings bond by complaining about the boss, or about a particularly demanding client. Bonding by griping feels a lot riskier with a virtual colleague, partly because you never know whether or how an online interaction might be recorded or logged, but also because you may not have an accurate read on what is wise or appropriate to share.

So I try to get the best of both worlds by picking common enemies that aren’t actual people. A looming deadline or a clogged supply chain may not be quite as scary as a band of nebulously European gunmen, but these “enemies” can still help me and my colleagues bond over a shared source of adversity.

Make it personal.

Even if you’re forging an online relationship for strictly professional purposes, it pays to let a little of your personal life shine through. In Die Hard, McClane and Powell bond over junk food and parenting, laying the groundwork for McClane to reach out to Powell for a little virtual comfort while he’s stalking criminals through a darkened building.

When I’m working with people who have packed meeting calendars, I’m sometimes tempted to skip this kind of personal chit-chat; I worry that talking about kids or TV or snack foods might make me seem frivolous, or just insufficiently busy. But heck, if John McClane can find time to talk about Twinkies while trying to evade a horde of gunmen, I can probably squeeze in a few words about the latest Ted Lasso while waiting for a call to get underway. Even if these personal chats are only short or occasional, it’s amazing how much they build rapport with my online colleagues—in a way that makes it easier for us to turn to one another for feedback and support.

Know the value of taking it offline.

I do so much of my work online—most of it for clients in another country and on another coast!—that it’s tempting to think I can do everything online. After all, it’s a hassle to put on meeting-worthy work clothes, and an even bigger hassle to take a six-hour plane ride to that meeting.

But Die Hard is a great annual reminder of how much face-to-face contact actually does matter to the way we build trust with our colleagues. Even if I can get 99% of my work done over email, text and video, that last 1% really matters—especially when it comes to cementing the relationships we build online.

Yes, McClane and Powell vanquish most of the bad guys, even though all their communication is over radio. But even if you can get all your work accomplished through virtual collaboration, it’s delightful to finally meet in person! That’s the delight that punctuates the movie, in a final scene that sees Powell and McClane finally meet in the flesh–just in time for Powell to shoot one last bad guy himself.

Rethinking rituals.

I hope your year ends with some wonderful rituals of your own—whether that looks like watching Die Hard or something with a lower body count.

This post was originally featured in the Thrive at Worknewsletter. Subscribe here to be the first to receive updates and insights on the new workplace.

Recent Comments